What You Need to Know About Prevention

By Mallory Black / Native Health News Alliance

SAN DIEGO — While colorectal cancer affects men and women of all racial and ethnic groups, it’s the second most common cancer among Northern Plains American Indians – a population with rates 53 percent higher than the general U.S. population. About one in 20 Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime.

SAN DIEGO — While colorectal cancer affects men and women of all racial and ethnic groups, it’s the second most common cancer among Northern Plains American Indians – a population with rates 53 percent higher than the general U.S. population. About one in 20 Americans will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetime.

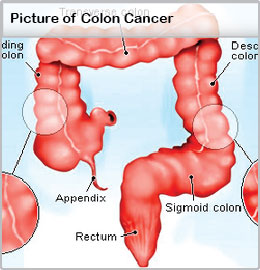

Colorectal cancer, also known as colon cancer, is a disease that develops in the colon or rectum. Abnormal growths, or polyps, can develop in these areas and can potentially become cancerous over time.

March is National Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month, and the American Indian Cancer Foundation, located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, is promoting awareness of colorectal cancer throughout the month. The Colon Cancer Alliance has designated March 6 as ‘Dress in Blue Day’ to raise awareness of the disease.

“Over the past 20 years, the U.S. population as a whole has been celebrating decreases in cancer mortality. Unfortunately, American Indian populations have not had the same good news, says Kris Rhodes (Ojibwe), executive director of the American Indian Cancer Foundation (AICAF), a non-profit dedicated to eliminating the cancer burdens on American Indian families. “This is largely the result of cancer diagnoses that are too late.

“AICAF sees opportunities to change that story with the promotion of screening to catch cancer early when it is easier to treat and survive, Rhodes says.

Because there are often no symptoms of early colorectal cancer, experts agree that a colonoscopy screening is one of the best forms of prevention, as early stage cancer can actually be removed during the screening. Peter Lance, deputy director of the University of Arizona Cancer Center, says the whole idea of cancer screenings is to prevent it.

“The reason we don’t want to wait until there are symptoms is because the cancer we can diagnose through screenings is [found] much earlier in their development, Lance says. “Most colon cancers develop from [non-cancerous] colon polyps.

While some people in Indian Country are still largely unaware of the risk of colorectal cancer, that’s changing every day, says Joy Rivera (Haudenosaunee), a community health worker with AICAF and former colorectal cancer screening navigator.

Rivera helps increase awareness of the importance of cancer screenings in American Indian urban and reservation communities. Her work includes dispelling myths about cancer screenings, which stem largely from past bad experiences.

Rivera helps increase awareness of the importance of cancer screenings in American Indian urban and reservation communities. Her work includes dispelling myths about cancer screenings, which stem largely from past bad experiences.

Some of the most common concerns she hears are whether the screenings hurt or if it’s as bad as people say it is.

Rivera says bad news spreads fast in the communities. “A lot of times people are saying they had a bad experience, painfulness, so what I try to do is realize they [likely] haven’t been apologized to. Things are better now.’

Rivera tries to help hesitant patients by reminding them that because American Indians make up such a small part of the general population, each life is a big deal. As soon as the walls come down, she says she stresses the importance of regular screenings and healthy living to be around for generations to come. “If you want to see your children or your grandchildren grow up, this cannot be ignored, Rivera adds.

One of Rivera’s most memorable moments happened when an American Indian man rode up to the clinic on a bicycle in the middle of winter, asking for a colon cancer screening.

He was diagnosed with colon cancer soon after.

Curious to know what brought him in that day, she asked and he told her he wanted to buy gifts for his children because the holidays were coming up. The clinic was offering a $25 gift card to anyone who came in for a cancer screening.

The man underwent several operations to remove the cancer, and the treatment seems to be working. “The last time I saw him, he was doing well. Rivera says.

Individuals have options for screenings, some of which are less invasive than others, but for many American Indians, the thought of ‘cancer’ or ‘cancer screenings’ can be intimidating. Fears about procedures, complications or pain can be perpetuated within small, close-knit Native communities.

David Perdue (Chickasaw), a gastroenterologist in Minneapolis, says most people just share a fear that the doctor could find something. Perdue says what many people don’t realize is when clinicians talk about cancer screenings, they’re really talking about cancer prevention.

“Some people would rather not know, which is something we’ve been really trying to impress on people; that really the intention of screening is not so much finding cancer, it’s finding polyps and getting those out before they turn into cancer, Perdue says.

Perdue says sometimes genetics play into the incidence of colon cancer and polyps are bound to occur. “But if you can get screened starting at age 50, or earlier if there’s a family history, that’s the best way to find polyps. It’s a lot easier to pull a weed when it’s small than when it’s big and rooted, he says.

Aside from colonoscopies, fecal occult blood tests can also screen for cancer signs in stool samples. They can be sensitive enough to detect bleeding from a polyp that hasn’t otherwise caused any symptoms or enough bleeding to change the color of the stool, but the tests are considered somewhat less effective than other screening methods.

The American Cancer Society recommends people receive screenings beginning at age 50. Research shows most colorectal cancers could have been prevented if more people participated in regular screenings. If colorectal cancer is found early, nine out of 10 patients survive, according to AICAF.

Still, many people are impacted by colorectal cancer every year. The American Cancer Society expected the disease to be diagnosed in nearly 72,000 men and 65,000 women in the U.S. in 2014 alone.

For some Native communities, the struggle in seeking cancer care sometimes involves another challenge: integrating traditional healing and beliefs with Western medicine.

Perdue understands traditional healers may have different feelings about cancer, but says he knows a traditional healer who reminds his own patients to get screened for colorectal cancer, otherwise he tells them, ‘‘It’ll take over.’

© Native Health News Alliance This is the first in an upcoming series of cancer stories produced by the Native Health News Alliance (NHNA), a partnership of the American Indian COC, Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) and the American Indian Cancer Foundation (AICAF).

NHNA creates shared health coverage for American Indian communities at no cost. Registered users can download additional print, web and audio content at www.nativehealthnews.com and publish as is or add their own reporting, highlighting important issues within the local Native community. NHNA services are free to all those who think good journalism has a positive impact in the lives of all of our readers, listeners, and viewers.